A Jazz Opera by Ted Rosenthal

In wartime Germany and Chicago, a story of tragedy, love and redemption

Dear Erich - A Jazz Opera by Ted Rosenthal

Dear Erich was commissioned by New York City Opera and received it's world premiere January 9-13, 2019, at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. Dear Erich was inspired by 200 newly discovered letters written in Germany between 1938 and 1941 by Herta Rosenthal to her son Erich, the composer's father. Dear Erich tells a refugee story for our times. How can a family cope as the walls of their nation's hatred close in around them? For those who escape, what lies ahead? Even in the land of the free, are they ever really free? What if they never learn the fate of loved ones left behind and the communications just stopped? What does closure mean, why does remembrance matter, where does hope come from?

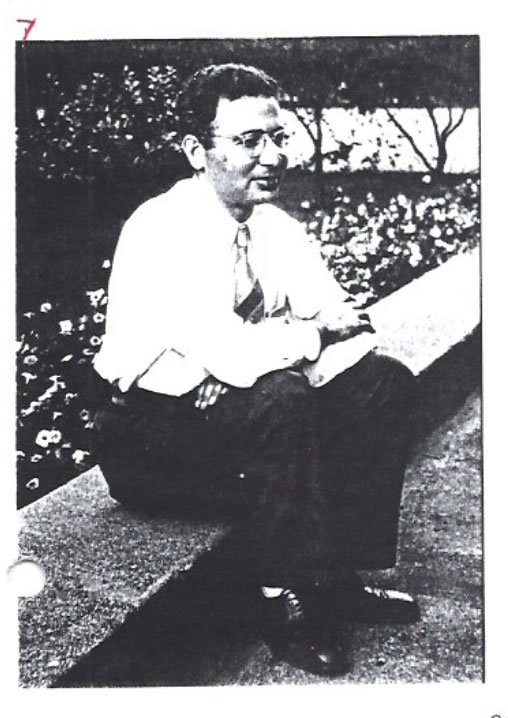

Erich, a Jewish academic, escaped Nazi Germany to the U.S. shortly before Kristallnacht. The opera tells the story of a family's dual fates. Erich's journey to a new life in the new world - his studies, jazz and love - while the situation deteriorates in Germany and his family ultimately meets their cruel demise at the hands of the Nazis. Frustrated and powerless to help them emigrate, Erich must live with deep survivor guilt which affects him in his relationships with his wife and children.

Dear Erich addresses these themes – walls and wars, refugees and immigrants, survivors and victims, the promise of a new world. Dear Erich asks what is found when a survivor forms a new family, and what gets lost when the next generation is untethered to the past? The opera's scenes of immigration and refugees in crisis raise moral dilemmas that resound to this day. Finally, Dear Erich stands for the power of remembrance, not just to honor the past but also to root us in the present and chart our future.

DEAR ERICH - A JAZZ OPERA BY TED ROSENTHAL

- Music by Ted Rosenthal

- Story by Ted Rosenthal

- Libretto by Ted and Lesley Rosenthal

- Inspired by letters by Herta Rosenthal and family

- Translated by Dr. Peter Schmidt

- Additional libretto/lyrics: Barry Singer, E.M. Lewis, Edward Einhorn

Dear Erich Press – Features and Reviews

Videos

Always Believe

Lili, Erich's wife, urges Erich to look forward and embrace their new life, family and children, despite his realization of losing his family in the Holocaust.

Land Ho!

Erich experiences the excitement of landing in the new world with its sights and sounds of freedom and democracy.

Everything My Father Never Told Me / Children of America

Freddy, Erich's son, laments that Erich never shared his past, causing much distance between them. Carmelita, Erich's nurse, explains the immigrant's desire to leave the painful past behind.

You Make Me Laugh

Erich and Lili are out on the town, Listening to jazz, dancing and falling in love.

Immigration Song

Herta, Erich's mother, and Erich desperately try to get her a visa to the US, but due to endless bureaucracy and unattainable requirements by US immigration officials, they fail. The Nazi grip grows tighter and the walls close in.

Kristallnacht Letter

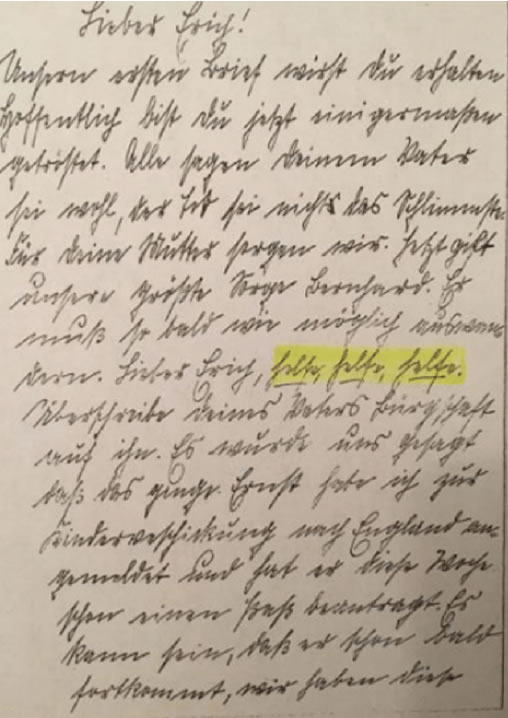

Herta writes to Erich, telling hIm that his father was taken during Kristallnacht. Though he was able to return, he was in weakened and sickly condition and died.

- Vocalists: Rachel Zatcoff, John Viscardi, Jessica Tyler Wright, Sharin Apostolou, Adam Klein, Elise Quagliata, Joshua Jeremiah, Dan Curran, Peter Kendall Clark

- Band: Angelo DiLoreto – Piano, Thomson Kneeland – Bass, Tim Horner – Drums

Archival Images

Dear Erich

A Jazz Opera by Ted Rosenthal

Synopsis

Act 1

Erich, a retired professor, is old and ill. He spends his days mostly isolated, attended by his nurse, Carmelita. He drifts in and out of consciousness, having "conversations" with Herta, his dead mother. Before he dies, Erich needs to resolve if he did enough to try to save her and the family from the Nazis. Adding to his misery, he was never able to learn her final fate. Erich's adult children, Freddy and Hannah, knowing their father is ill, dutifully visit. But the relationship among all three is strained and distant. Erich's survivor guilt and unwillingness to share himself and his history cause much of the family strife. Erich hints at his dilemma to his children. Freddy and Hannah remind him that they know nothing of the family he lost. Erich reluctantly agrees to share his past.

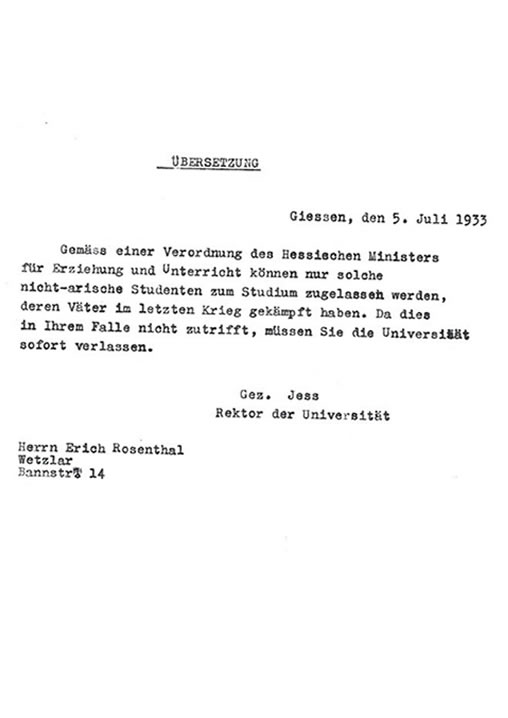

Flashback to Germany, 1938, Erich is ordered to leave his school because he is Jewish. Erich runs home, hurt and bewildered. Friedrich, his father, does not understand Erich's interest in academia and wants Erich to forget about school and join the family scrap metal business. But Erich tells Friedrich he has been accepted with a fellowship to the University of Chicago and that he will leave Germany.

Erich arrives in Chicago and senses the feelings of freedom and democracy and is tantalized, and a bit overwhelmed as he meets colorful characters in the US. Erich enters class for the first day, concerned whether he will be accepted. He thanks the professor for the opportunity to study in safety in the US and takes in the very different classroom scene. In his class folder Erich finds the first letter from his parents back in Germany. Herta is very concerned about him and Friedrich writes about the poor state of the family business and asks Erich about his prospects for a job. Erich looks up from the letter and realizes he has been noticed by his pretty and bright classmate, Lili.

Back in the present, Hannah and Freddy overhear Erich's "conversation" with his mother and notice he's reading a letter. They are astonished to learn from Carmelita that there are over 200 letters from Herta to Erich they never knew about. They plead with Erich to read the letters so they can know more family history. Erich starts to read the letter about Kristallnacht. Cut to Germany, 1938 – depiction of Kristallnacht. Freddy and Hannah listen in horror as Herta's letter narrates the death of Friedrich as a result of the pogrom.

Act II

Freddy reflects on Erich's revelations, his losses, and their impact on Freddy himself. Carmelita overhears and sings about her immigrant experience, and not wanting to burden her children by sharing her painful past.

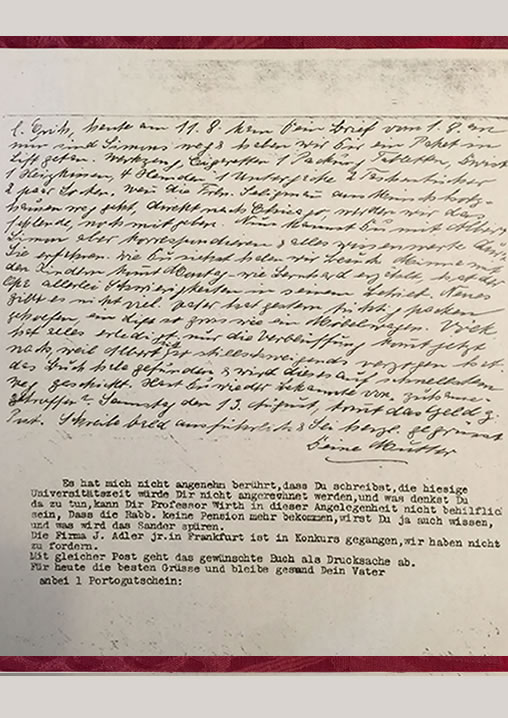

Cut to Chicago, 1940 - Erich and Lili are out on the town, enjoying jazz clubs and the vibrant nightlife. They listen, laugh, dance, and fall in love. Leaving the club, Erich remembers his family's perilous situation back home. Herta writes that the situation has gotten very bad. Erich needs to act quickly to help her with emigration. Herta and Erich each deal with US immigration officials on both sides of the Atlantic, but meet many obstacles. Erich writes his mother that he is trying his best. He also tells her that he and Lili will get married.

1942 - Erich and Lili get married, a joyous wedding with dancing – jazz and Hora. Erich imagines his mother joining in the wedding festivities and briefly walks away from the party, worrying about his family. Place Shift – Somewhere in Poland - a Death Camp. Erich's family is murdered.

Chicago, 9 months later - Hannah is born. Lili is joyful. Erich's joy is muted by the uncertainty of what happened to his mother. The letters have stopped. He is tortured wishing he could have done more to help. Lili encourages Erich to look ahead to their new life and family.

Present day - Freddy has traveled to Erich's hometown, Wetzlar, Germany, invited by Dr. Schmidt, the President of the Wetzlar Historical Society. Dr. Schmidt tells Freddy that in refurbishing the town synagogue, they found hidden letters there that were never sent, including one from Herta to Erich. On the way to the synagogue they see German teens hassling women in burqas. The youth shout that the women should go back where they came from. Dr. Schmidt and Freddy chase them away. Schmidt reflects on the importance of trying to be better than before and remaining vigilant. At the synagogue, they read Herta's last letter. She writes that she and the remaining family were ordered to board a relocation train on June 10, 1942. She expresses gratitude that Erich was able to leave when he did, and she urges him to live his life fully. Schmidt informs Freddy that this "relocation" train went to the Sobibor death camp in Poland. The passengers would have been killed shortly after arrival.

Cut to New York. Freddy and Hanna are at Erich's bedside. Freddy tells Erich he found out what happened to Herta. He shares her words of gratitude that Erich could leave and live his life. Freddy and Hannah beg Erich to forgive himself. Erich finally accepts. Erich hopes his children can forgive how distant and uncommunicative he was all those years. They reconcile. Erich dies. Though Erich couldn't rescue Herta, Freddy and Hannah vow to rescue her memory and keep it alive. Herta appears and warns them to "stand guard against hate." She asks them to remember her and her family's story to future generations. Dr. Schmidt joins, urging all to remember the past to ensure it is not repeated. Freddy, Hannah and all sing about the power of remembrance.

Dear Erich

A Jazz Opera by Ted Rosenthal

The Back Story

In May 2015, I was invited to attend the re-opening of a small refurbished Jewish religious school, the "Alte Judiche Schule," in my grandmother's hometown of Bad Camberg, Germany. The school had been abandoned and dilapidated since WW II, but was restored as a town project overseen by the Bad Camberg Historical Society, led by Doris Ammelung and Dr. Peter Schmidt. The town invited the descendants of the Jewish community to take part in the ceremonial re-opening of the school as a historic site. Shortly before leaving for Germany I went to the attic in my house where I had stored a box of letters written in Germany, (mostly) by my grandmother, Herta, to my father Erich, in Chicago. These letters, in German, were also stored in the attic of the house I grew up in. I kept the box after my father passed away, but never investigated its contents. My father escaped Nazi Germany in the spring of 1938, a few months before Kristallnacht. Most of his family including his parents and many cousins, perished. He said next to nothing about his wartime experiences and the family that he lost, and never discussed the letters.

During the visit to Bad Camberg I discussed the letters with Dr. Schmidt. In the rush to catch my flight I forgot to bring any with me, but Dr. Schmidt said I could send a few on later, he'd have a look, and be happy to translate. I scanned and emailed six to him - the final six - the last being written in November 1941. In August 2015, I received an email from Dr. Schmidt with the translations. Just a few lines into reading the first letter, the tears started to flow... A whole world began to open up, a world of family, family friends, people and places that were a fundamental part of my father's growing up. But my father never discussed the people, events, or the letters, no doubt because it was too painful. I conveyed this profound experience of getting to know this family, my family, to Dr. Schmidt. I told him there were more letters and asked him if he'd be willing to translate. He agreed, perhaps not knowing there were over 200!

In February 2016, I had to take 3 months off from performing to recover from an operation on my left arm. Fortunately, the operation was a complete success and I returned to my full schedule of performing. But in that period, I decided I would focus on composing. In these same months I was having amazing revelations through the translations of the "rediscovered" letters. Getting to know my grandparents and their personalities, learning about and getting to know aunts, uncles and cousins. Learning about their struggles, the frustration and ultimately the impossibility of emigration, the "walls closing in." My grandmother's letters, even with her understated language (being read by censors), wry sense of humor, and not wanting to alarm my father, captured so much and filled in so many holes in family history I knew almost nothing about. These revelations, and the events that surrounded them, were the inspiration for my setting out to compose my jazz opera, "Dear Erich."

As a composer, one of the most intense parts of the process was putting music to my grandmother's letters. Composing music to the letter where she breaks the news to my father of the death of his father (her husband) after Kristallnacht was particularly intense. The words put to music magnify the emotion; hearing them sung by the wonderful artists associated with New York City Opera has been incredibly moving. And to experience the singers being moved by the music and the subject matter is doubly gratifying. In crafting the story, for the sake of effective drama, some elements are exaggerated or made up. But even with a good deal of dramatic license, "Dear Erich" is a family story. As in the opera, the act of remembrance is both emotionally intense and healing.

For more on "The Back Story", visit Ted Rosenthal's blog

Upcoming Performances

- March 2, 2025, 7:00 pm

Dear Erich Concert Performance

Tilles Center, Krasnoff Theater, LIU, Brookville, Long Island, NY

Featuring 7 vocalists from the NYC Opera premiere

and the Ted Rosenthal Trio

Visit Website for More Information

Spring, 2025, Book release: Erinnerungskulturen und Demokratiebildung (Cultures of Remembrance and Democracy,

Interdisciplinary Music Pedagogical Perspectives.) The themes and music of "Dear Erich" are featured in this book which discusses: How can musical-aesthetic education enable expanded experiences in the context of history and democracy? The volume is shows how music and interdisciplinary approaches can contribute to the discussion of cultures of remembrance. Including chapters by Ted and Lesley Rosenthal.

- An educational version of Dear Erich is also being developed for students.

Read Rosenthal's Blog Post "Sharing Dear Erich with Young People"

Previous Performances

- August 6, 2022

Dear Erich Concert Performance

Mahaiwe Theater, Great Barrington MA

Featuring 7 vocalists from the NYC Opera premiere and the Ted Rosenthal Trio

- June 1, 2022

Dear Erich Presentation

World Justice Forum, The Hague, NL

- Saturday, April 2, 2022, 8:15 pm

Dear Erich concert performance

Featuring vocalists from the NYC Opera premiere and The Ted Rosenthal Trio,

Charter Oak Cultural Center

Hartford, CT

- January 27, 2021

Dear Erich Performance/Presentation Live Stream

Seattle Holocaust Center for Humanity

Watch on Youtube

- March 3, 2020

Dear Erich Talkback and Excerpts, "Letters to Erich"

Nicholas Music Center, Rutgers University

85 George Street, New Brunswick, NJ

Visit Website for More Information

- January 12, 2020

Dear Erich Showcase

Selections from Dear Erich performed by stars from the NYC Opera premiere and the Ted Rosenthal Trio

APAP Conference

Hilton Hotel, Regent Parlor Ballroom, 1335 6th Ave, NYC

Visit Website for More Information

- November 6, 2019 Dear Erich - Selections/Talkback Port Washington Library, Port Washington, NY

- October 27, 2019 Dear Erich Presentation - Selections/Talkback Ted Rosenthal with vocalists Glenn Seven Allen and Sishel Claverie Congregation Gates of Heaven, Schenectady, NY

- August 26,2019 Southampton Arts Center - Dear Erich Concert Presentation

- June 4, 2019, Copenhagen Synagogue, Denmark - Dear Erich Concert Presentation

- May 3, 2019, Westchester Reform Temple - Dear Erich Excerpts and Talkback with Ted Rosenthal

- May 1, 2019, Center for Jewish History - Dear Erich Concert Presentation

- World premiere of Dear Erich

January 9 - 13, 2019, by New York City Opera

At the Museum of Jewish Heritage, NYC - July 25, 2018, Usdan Summer Camp for the Arts. Dear Erich Educational Event. Excerpts and Talkback with the composer.

- January 8, 2018, New York City Opera Reading at Clark Studio Theater, Lincoln Center

- October 16, 2017, Dear Erich Excerpts and Presentation, US Memorial Holocaust Museum, NY Tribute Gala

- July 20, 2017, Usdan Summer Camp for the Arts. Dear Erich Educational Event. Excerpts and Talkback with the composer.

About The Composer

Ted Rosenthal

Ted Rosenthal is one of the leading jazz pianist/composers of his generation and has performed worldwide as soloist, with his trio, and with many jazz greats. Rosenthal composes music ranging from jazz tunes to orchestral works (two jazz piano concertos) and ballet scores. The recipient of three NEA grants, Rosenthal has been commissioned by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, The Park Avenue Chamber Symphony, Dallas Black Dance Theatre and more. He has also been a featured soloist with major American orchestras including the Detroit Symphony. Winner of the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition, Rosenthal has released 15 CDs as a leader. His latest, "Rhapsody in Gershwin," reached #1 on iTunes and Amazon. www.tedrosenthal.com